Healthy Leadership, Spiritual Living

Spiritual Perspectives on the Coronavirus Pandemic

We are living in the midst of a shocking world-wide crisis. At this point, we don’t know how long it will last, how much physical suffering and economic devastation it will create, or how many lives it will take. At a time like this, when people are reeling with job losses, fears about the future, fears about their health, and fears about loved ones … what we need most of all is the comfort and encouragement of community.

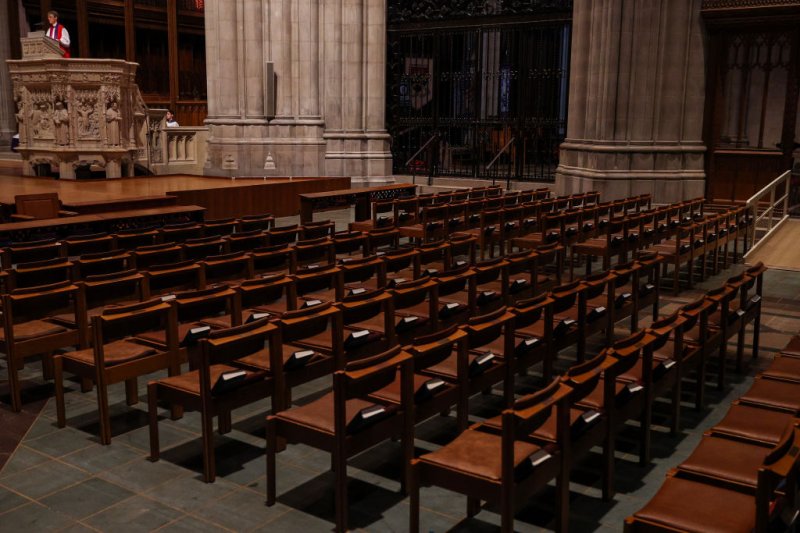

And that’s where this crisis is so perverse: the requirements of “social distancing” are cutting us off from the connections we so desperately need.

With physical presence restricted, we’re having to be creative and find ways of supporting each other through phone calls, emails, and video chatting. In our churches, we’re exchanging face to face small group gatherings and worship services with video conferences and virtual worship services. It’s weird.

In the midst of it all, there are spiritual questions to wrestle with, and mental health struggles — especially depression, loneliness, and anxiety — to work through.

Like many of you, I’ve been following the news closely — probably more than is good for me. I’ve been reading a variety of articles from authors of various stripes in an effort to understand better for myself what’s happening around me, so I can hopefully offer support and encouragement to others.

Here’s what what we need to remember: While we’re in the midst of a crisis, it’s nearly impossible to understand it. Insight and wisdom come later. Right now we have to muddle through, putting one step in front of the other.

Don’t get me wrong: There is important wisdom being shared. Amidst the deluge of blog posts, magazine articles, and social media updates, there are many helpful things being written.

In that spirit, I thought it might be helpful this week to draw your attention to four different articles that have been helpful to me, in hopes that you might find something for yourself too. For each, I give a short synopsis, some quotes, and a link to the original article. I hope this helps!

“The Discomfort You’re Feeling Is Grief”

Source: Harvard Business Review

David Kessler is the world’s foremost expert on grief. He co-wrote with Elisabeth Kübler-Ross “On Grief and Grieving: Finding the Meaning of Grief through the Five Stages of Loss.” His new book adds another stage to the process, “Finding Meaning: The Sixth Stage of Grief.”

This article contains a brief interview with him, which talks about the current pandemic, and how it creates distress … much of which is grief. Here are some highlights:

“We know this is temporary, but it doesn’t feel that way, and we realize things will be different. Just as going to the airport is forever different from how it was before 9/11, things will change and this is the point at which they changed. The loss of normalcy; the fear of economic toll; the loss of connection. This is hitting us and we’re grieving. Collectively. We are not used to this kind of collective grief in the air.”

“Anticipatory grief is that feeling we get about what the future holds when we’re uncertain. Usually it centers on death. … With a virus, this kind of grief is so confusing for people. Our primitive mind knows something bad is happening, but you can’t see it. This breaks our sense of safety. We’re feeling that loss of safety. I don’t think we’ve collectively lost our sense of general safety like this.”

How do you overcome this grief?

“Anticipatory grief is the mind going to the future and imagining the worst. To calm yourself, you want to come into the present. This will be familiar advice to anyone who has meditated or practiced mindfulness but people are always surprised at how prosaic this can be. …This really will work to dampen some of that pain.

“You can also think about how to let go of what you can’t control. What your neighbor is doing is out of your control. What is in your control is staying six feet away from them and washing your hands. Focus on that.

“Finally, it’s a good time to stock up on compassion. Everyone will have different levels of fear and grief and it manifests in different ways.”

Christianity Offers No Answers About the Coronavirus. It’s Not Supposed To

Source: NT Wright, in Time Magazine

This article by theologian NT Wright offers a helpful, balanced response to the theological questions raised by the pandemic: “Why is this happening?” “Where is God?” Wright is very clear is stating: WE DON’T KNOW. The Bible seldom gives those kind of explanations about God’s purpose in tragedies.

He writes:

“No doubt the usual silly suspects will tell us why God is doing this to us. A punishment? A warning? A sign? These are knee-jerk would-be Christian reactions in a culture which, generations back, embraced rationalism: everything must have an explanation. But supposing it doesn’t? Supposing real human wisdom doesn’t mean being able to string together some dodgy speculations and say, “So that’s all right then?” What if, after all, there are moments such as T. S. Eliot recognized in the early 1940s, when the only advice is to wait without hope, because we’d be hoping for the wrong thing?

“Rationalists (including Christian rationalists) want explanations; Romantics (including Christian romantics) want to be given a sigh of relief. But perhaps what we need more than either is to recover the biblical tradition of lament. Lament is what happens when people ask, “Why?” and don’t get an answer. It’s where we get to when we move beyond our self-centered worry about our sins and failings and look more broadly at the suffering of the world.”

Then Wright goes on to explain more about what biblical lament is, and gives examples of it from the book of Psalms. He ends the article with this:

“It is no part of the Christian vocation, then, to be able to explain what’s happening and why. In fact, it is part of the Christian vocation not to be able to explain—and to lament instead. As the Spirit laments within us, so we become, even in our self-isolation, small shrines where the presence and healing love of God can dwell. And out of that there can emerge new possibilities, new acts of kindness, new scientific understanding, new hope. New wisdom for our leaders? Now there’s a thought.”

Where Is God in a Pandemic?

Source: James Martin, in NY Times magazine

James Martin is a Jesuit Priest in New York, an author of many books, and editor of America magazine. Of the four articles I’m profiling here, Martin’s goes into the most detail about the big question of suffering: Why is God letting this happen? N.T. Wright simply said, “We don’t know” … and instead recommended we focus right now on lament instead.

The age-old question of “the problem of evil and suffering” has dogged theologians and philosophers since the beginning of time. As Martin rightly points out in this article (and Wright pointed out in his), there’s no way of answering this question in a satisfactory way. Martin, however adds another nuance: Christian teaching does, however, offer a unique perspective about suffering, which many have found to be helpful and comforting.

I quote from it at length below:

“In just the past few weeks, millions have started to fear that they are moving to their appointment with terrifying speed, thanks to the Covid-19 pandemic. The sheer horror of this fast-moving infection is coupled with the almost physical shock from its sudden onset. As a priest, I’ve heard an avalanche of feelings in the last month: panic, fear, anger, sadness, confusion and despair. More and more I feel like I’m living in a horror movie, but the kind that I instinctively turn off because it’s too disturbing. And even the most religious people ask me: Why is this happening? And: Where is God in all of this?

“The question is essentially the same that people ask when a hurricane wipes out hundreds of lives or when a single child dies from cancer. It is called the “problem of suffering,” “the mystery of evil” or the “theodicy,” and it’s a question that saints and theologians have grappled with for millenniums. The question of “natural” suffering (from illnesses or natural disasters) differs from that of “moral evil” (in which suffering flows from the actions of individuals — think Hitler and Stalin). But leaving aside theological distinctions, the question now consumes the minds of millions of believers, who quail at steadily rising death tolls, struggle with stories of physicians forced to triage patients and recoil at photos of rows of coffins: Why?

“Over the centuries, many answers have been offered about natural suffering, all of them wanting in some way.

(Now I’m inserting the headlines … the actual article doesn’t make the structure so explicit.)

Option 1 – God is testing us.

“The most common is that suffering is a test. Suffering tests our faith and strengthens it: “My brothers and sisters, whenever you face trials of any kind, consider it nothing but joy, because you know that the testing of your faith produces endurance,” says the Letter of James in the New Testament. But while explaining suffering as a test may help in minor trials (patience being tested by an annoying person) it fails in the most painful human experiences. Does God send cancer to “test” a young child? Yes, the child’s parents may learn something about perseverance or faith, but that approach can make God out to be a monster

Option 2 – God is punishing us.

“So does the argument that suffering is a punishment for sins, a still common approach among some believers (who usually say that God punishes people or groups that they themselves disapprove of). But Jesus himself rejects that approach when he meets a man who is blind, in a story recounted in the Gospel of John: “Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?” “Neither this man nor his parents sinned,” says Jesus. This is Jesus’s definitive rejection of the image of the monstrous Father. In Luke’s Gospel, Jesus responds to the story of a stone tower that fell and crushed a crowd of people: “Do you think that they were worse offenders than all the others living in Jerusalem? No, I tell you.”

“The overall confusion for believers is encapsulated in what is called the “inconsistent triad,” which can be summarized as follows: God is all powerful, therefore God can prevent suffering. But God does not prevent suffering. Therefore, God is either not all powerful or not all loving.

Option 3 – We don’t know God’s purpose in it.

“In the end, the most honest answer to the question of why the Covid-19 virus is killing thousands of people, why infectious diseases ravage humanity and why there is suffering at all is: We don’t know. For me, this is the most honest and accurate answer. One could also suggest how viruses are part of the natural world and in some way contribute to life, but this approach fails abjectly when speaking to someone who has lost a friend or loved one. An important question for the believer in times of suffering is this: Can you believe in a God that you don’t understand?

“But if the mystery of suffering is unanswerable, where can the believer go in times like this? For the Christian and perhaps even for others the answer is Jesus.”

Comfort offered in Christian theology — “God with us”

“Christians believe that Jesus is fully divine and fully human. Yet we sometimes overlook the second part. Jesus of Nazareth was born into a world of illness. In her book “Stone and Dung, Oil and Spit,” about daily life in first-century Galilee, Jodi Magness, a scholar of early Judaism, calls the milieu in which Jesus lived “filthy, malodorous and unhealthy.” John Dominic Crossan and Jonathan L. Reed, scholars of the historical background of Jesus, sum up these conditions in a sobering sentence in “Excavating Jesus”: “A case of the flu, a bad cold, or an abscessed tooth could kill.” This was Jesus’s world.

“Moreover, in his public ministry, Jesus continually sought out those who were sick. Most of his miracles were healings from illnesses and disabilities: debilitating skin conditions (under the rubric of “leprosy”), epilepsy, a woman’s “flow of blood,” a withered hand, “dropsy,” blindness, deafness, paralysis. In these frightening times, Christians may find comfort in knowing that when they pray to Jesus, they are praying to someone who understands them not only because he is divine and knows all things, but because he is human and experienced all things.

“But those who are not Christian can also see him as a model for care of the sick. Needless to say, when caring for someone with coronavirus, one should take the necessary precautions in order not to pass on the infection. But for Jesus, the sick or dying person was not the “other,” not one to be blamed, but our brother and sister. When Jesus saw a person in need, the Gospels tell us that his heart was “moved with pity.” He is a model for how we are to care during this crisis: with hearts moved by pity.”

Coping With Anxiety in a Pandemic

Source: J. Dana Trent, in Sojourners Magazine

This article seeks not so much to explain why the pandemic is here … its focus is to help Christians deal with it. Trent’s strategy for facing the anxiety created by the pandemic — even though the words aren’t used — is faith and trust, mediated through the practice of meditation and acceptance. I wanted to add her article, because it contains some helpful reminders about how stress works, and how it flares up in times like this.

Trent writes (once again, the headlines are my insertion):

“As I write this, COVID-19 cases are soaring in real time … [and] we are experiencing anxiety we haven’t known since 9/11. We haven’t felt this helpless, fragile, and mortal for nearly a generation.

“And it shows. Mental Health America, a community-based nonprofit, reports a nearly 20 percent increase in clinical anxiety screenings beginning in February. The CDC dedicated an entire subpage to managing COVID-19 stress.

The Science of Stress

“To be sure, it’s normal for all of us to feel a pandemic’s urgency. The brain does not discriminate against triggers. Once we encounter stress, the body responds and anxiety is a natural response.

“Two years ago, my mother was diagnosed with a sudden and traumatic illness that landed her in the intensive care unit (ICU). My brother and I remained at her bedside and she died just 14 days after her diagnosis. Though my theological education and ministry includes service as an ICU chaplain specializing in care for the dying and grieving, I found myself in a 24/7 panic after her death. I couldn’t sleep, eat, or think. I didn’t realize it at the time, but the acute anxiety was my brain carrying over a hyperalert posture of constant worry and exhaustion.

“I was advised to calm my body’s automatic response to anxiety through deep breathing. Though I resented this remedy, I began the meditation practice. More importantly, I learned why deep breathing works and I wrote a book on how to make it work for all of us.

“Our body’s homeostasis is controlled by the autonomic nervous system, comprised of two parts: sympathetic and parasympathetic. These two systems regulate our respiratory and circulatory processes, among other essential functions. The sympathetic division is the “fight-or-flight” response that prepares our bodies to cope with urgent situations like COVID-19. It releases norepinephrine to increase our pulse and blood pressure, diverting essential resources to the heart, lungs, and muscles. Anxiety fuels this system, so much so that we feel we are always on alert mode.

How do we cope?

“But anxiety is not sustainable — it never was — especially in what is likely to become a months-long global crisis. Even when we move through COVID-19 together — and we will —there will always be another crisis. The key, then, is learning simple and practical ways to help us cope.

“So, while our sympathetic system feels sorry for us and feels it must remain “on call” especially mid-coronavirus, it is our parasympathetic division that is the real key to coping. This system, stimulated by deep breathing, releases acetylcholine to slow down the heart rate, lower blood pressure, and relax airway muscles, soothing anxiety.

“While it’s normal to fear in these moments, our fear is not isolated to the virus. It can also be tied to unexpected isolation. It’s our reluctance to face what 17th-century mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal, author of Pensées, names as the root of all of humanity’s problems: our inability to sit in a room alone. We are now in a room alone. What are we going to do about it?

“In his book, The Plague, Algerian-French author and philosopher Albert Camus wrote of our inescapable death and how a mere acknowledge of it is a revelation, not an invitation into despair. While Camus’s prose may not be your desired binge-worthy pandemic read, his existential notion of “the absurdity of life” is redemptive. In other words, when we name our fragility, we are free to do the “inside work.” We are liberated to be practical and patient. Free-floating anxiety loses its grip. As Rev. Benjamin Boswell puts it, “Mortality is our a pre-existing condition.”

I want to stop and add my own emphasis to this very subtle, yet important point: Albert Camus uses the phrase “the absurdity of life,” which might cause Christians to recoil … but don’t react against it too quickly. We have the idea drummed into our heads that “God is in control,” “Everything happens for a reason,” and “God is working everything out according to his plan.” But the problem is … this plan is mysterious and in many respects unknowable to us. The Apostle Paul reminds us in I Corinthians 13:12 that, in this life, we don’t see or understand things clearly: “For now we see only a reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I am fully known.”

It’s another variation on what NT Wright and James Martin said: sure there’s a purpose for what’s going on here, but we may very well not know it. It’s not our job to know, it’s not within our capacity to know. Trent’s suggestion, in light of this “not knowing,” is to practice acceptance, and learn to live with inner peace.

“Might this pandemic be the “rich lens of attention” Mary Oliver wrote of? Or, the call to “emancipate ourselves from mental slavery” Bob Marley invited us to? Were we to look to our wise ones, the modern and ancient mystics, Jesus, Buddha, St. Teresa of Avila, Sojourner Truth, Gandhi, and King, we would encounter a return to the ABCs of inner, contemplative work that softens the anxiety of the time. When we sit at the feet of these gurus, we learn that, when confronted with crisis, they chose the internal journey as much as the external. Anxiety did not get the best of them; they pondered the difficult questions of the human condition, rather than filling the time with a temporary, self-perpetuated frenzy cure that does not endure. They sat with themselves in order to sit with others. It’s so basic, and yet so difficult for us.

“For both the privileged remote-workers and the newly jobless, our proverbial and literal calendars are now cleared. We’ve stepped off the physical roller coaster only to be confronted with the cure to the absurdity of life: being present. Anxiety is reaching into the future and worry about what is unknown. While it’s normal, we are also called to sit in a room by ourselves and cope with our pre-existing condition.”